Report of the Department of Justice on January 13, 2021 Use of Force by New Castle County Police Department

Introduction from the Attorney General

On January 13, 2021, three officers from the New Castle County Police Department approached Lymond Moses in the area of Rosemont Avenue and East 24th Street in Wilmington. Following a brief interaction, Mr. Moses fled and, after being cornered on a fenced-off street, turned around and accelerated forward in an apparent attempt to flee. The events that happened next unfolded in a matter of just four (4) seconds. Two of the three officers fired at Mr. Moses’ vehicle, ultimately killing him. Those four seconds have, for nearly a year, been the focal point of intense public discussion and of an in-depth investigation by the Delaware Department of Justice (DOJ) and, subsequently, by an international law firm retained to review whether the evidence would support criminal charges. The enclosed report details that investigation’s findings and recommendations.1

This has been one of the most extraordinary and exhaustive use of force investigations that the DOJ has ever conducted. In addition to an excellent and thorough review of the facts by the Division of Civil Rights and Public Trust (DCRPT) – a review which included police and witness interviews, body camera footage, vehicle crash data, and medical forensics – the DOJ was fortunate to have the expertise and experience of outside investigators, led by Zane Memeger, who previously served as the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania from 2010 to 2016 and successfully prosecuted several federal corruption and public trust cases. We were also fortunate that Nate Andrisani, a former Philadelphia Assistant District Attorney, was part of the independent team that reviewed the facts of this case.

The review conducted by Mr. Memeger and his colleagues at Morgan, Lewis & Bockius (MLB) concluded that the laws in place at the time of the shooting would not support a reasonable likelihood of conviction against any of the officers involved in this incident. DCRPT made the same recommendation, and I agree with both.

I also retained a policing expert, Sean Smoot of 21CP (21st Century Policing) Solutions, a team of national police chiefs, community leaders, social scientists and others who work with communities, cities, and police departments to make public safety work better for everyone. Mr. Smoot is a former police commissioner in Illinois and is also a practicing attorney.

At my request, 21CP and MLB formulated several frank proposals on how to prevent this tragedy from reoccurring in the future. This body of recommendations includes changes to NCCPD training protocols so that future officers – whose decisions to use force are almost always split-second evaluations based on muscle memory and training – are prepared to keep themselves and others safe. Of particular note is the need for training that discourages the ineffective and dangerous practice of firing at moving vehicles, which has already been banned in major police departments from New York to Los Angeles. Such use of force is unlikely to disable a vehicle; dangerous to officers who may be in harm’s way; and dangerous to the driver, passenger, and bystanders, if a driver loses control. I will refer the recommendations to the Council on Police Training for their consideration as part of ongoing efforts to establish a uniform statewide use of force policy, which was recommended unanimously by the Law Enforcement Accountability Task Force earlier this year. I also recommend that the legislature review and consider amending 11 Del. C. § 467(c)(1)—which allows deadly force to disable moving vehicles—to align it with model police policies that ban shooting at moving vehicles except in some rare situations.2

I encourage you to read the MLB report thoroughly. The questions it answers are difficult and its findings may not be popular in all corners. But this case demands we face these hard questions. It has gone directly to the heart of the national debate over police use of force; has raised tremendous local public interest in what happened that night; and has begged the question of whether that which is lawful is also necessary and just. These questions are extraordinary, unavoidable, and vital; and our duty to the public trust requires our inquiry to answer them honestly, thoroughly, and independently beyond reproach.

My duty as Attorney General – the duty of this entire Department – is not to do what is expedient or popular with one side or another. Nor, for that matter, is it to avoid difficult conclusions. There will be those who believe we should press charges irrespective of our findings; but that asks us to violate our ethical, statutory, and constitutional obligations to prosecute only when there is a reasonable likelihood of conviction at trial. The law in place at the time is what controls our decision. There will also be those who take exception to the MLB report’s characterization of police training, judgment, and public statements; but this, too, asks us to violate our duty to the public by approaching questions of justice clinically and conflating that which is lawful with that which is right. Telling the truth – the whole truth – is always right, but rarely popular.

The question left unanswered is whether and how we can find the path forward to trust, accountability, and transparency. If there is anything that everyone can agree upon, it is that the status quo is unsustainable. Progress is not only achievable, but necessary. And that progress will be hard to win; indeed, today it may seem out of reach to some. But I believe it is possible. And I remain committed to moving us closer to a future where the answers to these questions are more clear, these investigations are less regular, and these tragedies are prevented altogether.

Kathleen Jennings

Delaware Attorney General

1 Since June 2020, DOJ policy has been to publish material and relevant evidence in every DCRPT use of force report. These are the only investigations in which the DOJ releases evidence prior to trial, let alone when no trial is being pursued. My view – and the view of many – is that these cases, and the questions they so often engender, are extraordinary and that their impact on the public trust demands that the public can see what our investigators see. Pursuant to that policy, the online edition of the MLB report features material and relevant evidence that both DCRPT and MLB reviewed, including unedited body camera footage, summaries of police interviews, and vehicle data.

2 See, e.g., Delaware Police Chiefs’ Council model policy: “Firearms shall not be discharged at a moving vehicle or from a moving vehicle unless: (1) a person is threatening the officer or another person with deadly force by means other than the vehicle; or (2) the vehicle is operated in a manner that would lead a reasonable officer to believe it creates a substantial risk of serious physical injury or death to the officer or another person, and all other reasonable means of defense have been exhausted (or are not present or practical), which includes moving out of the path of the vehicle.”

Morgan, Lewis & Bockius Report

In the early morning hours of January 13, 2021, three New Castle County police officers approached Lymond Moses (hereinafter, “Mr. Moses”) as he appeared to be sleeping behind the wheel of his car with the engine running. The officers saw that Mr. Moses was in possession of marijuana—a misdemeanor that the officers told Mr. Moses they had no interest in pursuing. Nevertheless, the dynamic interaction escalated very quickly to a dangerous situation: Mr. Moses refused to comply with the officers’ instructions to get out of his vehicle; Mr. Moses drove away from the officers until he reached a dead end; the officers pursued Mr. Moses in their vehicles, leaving their vehicles and drawing their firearms once they reached the dead end; Mr. Moses turned his car around, fully stopped with his headlights pointed at the officers, and then four seconds later proceeded to drive at a high rate of speed causing his tires to screech in the direction of the officers in an apparent attempt to escape; one of the officers discharged his weapon seven times while aiming at the windshield, driver’s window, and the back of Mr. Moses’s car; Mr. Moses was shot in the head, causing his vehicle to swerve toward a second officer; and that second officer discharged his weapon twice toward the swerving vehicle. Less than one minute passed between when Mr. Moses first drove his car away from the officers and when the last shot was fired. Mr. Moses succumbed to his injuries and died.

The New Castle County Police Department and the Delaware Department of Justice, Division of Civil Rights and Public Trust (“DCRPT”) conducted independent investigations into the use of deadly force by the officers against Mr. Moses. The Delaware Department of Justice engaged Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP (“Morgan Lewis”) 1 to conduct an independent review of the investigation materials, analyze the facts as determined by the Department of Justice’s investigation, and the applicable law that relates to a police officer’s use of deadly force and to provide advice and recommendations in connection with the two following questions:

- When applying the law to the facts of this case, is there a reasonable likelihood of conviction if the State were to charge one or more of the officers?

- What, if any, suggestions can we make to improve policies, training and police practices moving forward to avoid similar results in the future?

Morgan Lewis reviewed a wide variety of evidence: video footage, dispatch recordings, witness interviews, police interviews, scene photos, police reports, autopsy and toxicology reports, policies and procedures, training records, and forensic firearms reports.2 By agreement, Morgan Lewis did not receive or review any statements the officers may have made pursuant to Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.S. 493 (1967).3 Both DCRPT’s and Morgan Lewis’s investigation focused on whether any of the New Castle County police officers should be charged with a criminal offense. Morgan Lewis has determined that there is no reasonable likelihood of convicting any of the three officers of a criminal offense in connection with the shooting death of Mr. Moses. The State would have to overcome a legal justification defense in this case because there is credible evidence that the two officers who fired their weapons (Patrolman Roberto Ieradi, Corporal Robert Ellis) reasonably believed that doing so was necessary to protect either themselves or others against death or serious physical injury. Under Delaware’s deferential legal standard4 for the use of deadly force by a law enforcement officer, each officer’s subjective belief that using deadly force was necessary to protect themselves or others triggers a legal justification defense and is enough to assure that there is no reasonable likelihood of achieving a conviction if any of these officers were charged with a criminal offense.5

When conducting investigations of deadly force incidents to determine whether such force constituted a criminal act, we understand that the DCRPT’s report of findings normally does not:

- establish, enforce, or comment on internal policies on the proper use of deadly force by law enforcement officers; or

- express opinions whether an involved officers’ actions complied with departmental policies or procedures.

The circumstances around this particular incident, however, are concerning and demand consideration of how these officers were trained and, notwithstanding any potential violations of criminal law, if there were deficiencies in the New Castle County Police Department’s policies and training that should be corrected in light of the shooting of Mr. Moses to prevent similar incidents from happening in the future.

The events of January 13, 2021, and the death of Mr. Moses raise broader questions regarding police use of force tactics in Delaware, specifically what force can and should be used against moving vehicles. Delaware is not the only state to grapple with these circumstances, and one of the key questions in the national discussion over officer use of force is whether discharging a firearm at a moving vehicle is an appropriate and effective tactic.6 The emerging consensus is that the answer is no; firing at a moving vehicle is not only ineffective, but also often places the public, the target of the use of force, and, in fact, the officers themselves in greater danger.7 We suggest that the Delaware Department of Justice encourage Delaware’s police departments and law enforcement agencies to both (i) revisit their policies regarding what force can be used against moving vehicles; and (ii) if needed, revise their use of force training to ensure that their officers have the tools, clarity, and insight to safely work within their communities.

We understand that the Delaware Department of Justice has engaged experts from 21CP Solutions—a team of seasoned experts on policing that work with law enforcement agencies and communities—to address the need for reforming Delaware law enforcement agencies’ policies on use of force against a moving vehicle and the use of force training law enforcement officers receive. Given the circumstances that surrounded Mr. Moses’s death, and the deficiencies in the New Castle County Police Department’s use of force trainings and policies that we believe contributed to those circumstances, we agree with the Department of Justice’s decision to engage these experts. Our independent review of DCRPT’s shooting investigation leads us to believe that Mr. Moses’s death could have been avoided if better policing tactics were employed and the officers were provided with more effective use of force training. Addressing flawed policies and inadequate training, including gaps in use of force measures, will not only prevent incidents like these from continuing to happen, but increase the safety of members of law enforcement officers and the public.

Facts

As outlined above, Morgan Lewis performed an independent review of the investigative file on the January 13, 2021 incident.

On January 13, 2021, New Castle County Police Patrolman Roberto Ieradi, Corporal Robert Ellis and Officer Sean Sweeney-Jones were on patrol in the Riverside neighborhood around Rosemont Avenue in Wilmington, looking for stolen vehicles because of a recent pattern of stolen vehicles being used in shootings and robberies. Around Rosemont Avenue and East 24th Street, Corporal Ellis observed a vehicle parked on the side of the road, with its engine idling, inside lights on, and a driver that he believed to be sleeping. Corporal Ellis waited for Officers Ieradi and Sweeney-Jones to arrive before approaching the vehicle. Ieradi approached the driver’s window, Ellis approached the passenger’s window, and Sweeney-Jones positioned himself behind Ellis on the passenger’s side.

As seen in the bodycam footage, Officer Ieradi reached through the driver’s window with his baton to turn off the vehicle. Ellis and Ieradi then opened up the driver-side and front passenger doors to the vehicle and began giving simultaneous commands to Mr. Moses. The officers told Mr. Moses that they were in the area looking for stolen vehicles and that they noticed him in his vehicle and wanted to check on him to see if he was okay. In their interviews, the officers noted that when Mr. Moses woke up, he appeared agitated, confused, was sweating profusely, and appeared out of breath. Those descriptions were confirmed by the bodycam footage, although the footage also captured the officers’ manner of speaking simultaneously over each other, which likely added to Mr. Moses’s confusion and made compliance with the officers’ directions less likely. They also noted that he was clenching his fists and was slurring his words. Officer Ieradi stated that he believed that Mr. Moses was intoxicated or otherwise under the influence of a controlled substance, and asked Mr. Moses to step out of his car so they could check on him. The bodycam footage confirmed that Mr. Moses appeared disoriented and proceeded to make disjointed comments including that he was okay; his car was not a stolen vehicle; he was just sitting outside his mom’s house; and he refused to leave the car. The officers observed a bag of marijuana in the front console, told Mr. Moses that they were not concerned about “just weed,” and that they just wanted him to step out of the car to make sure that he was okay. Mr. Moses then started his car again, put his car in drive, and began to pull away from the officers, causing both the driver-side and passenger doors to close. All three officers returned to their patrol SUVs and pursued Mr. Moses down Rosemont Avenue.8

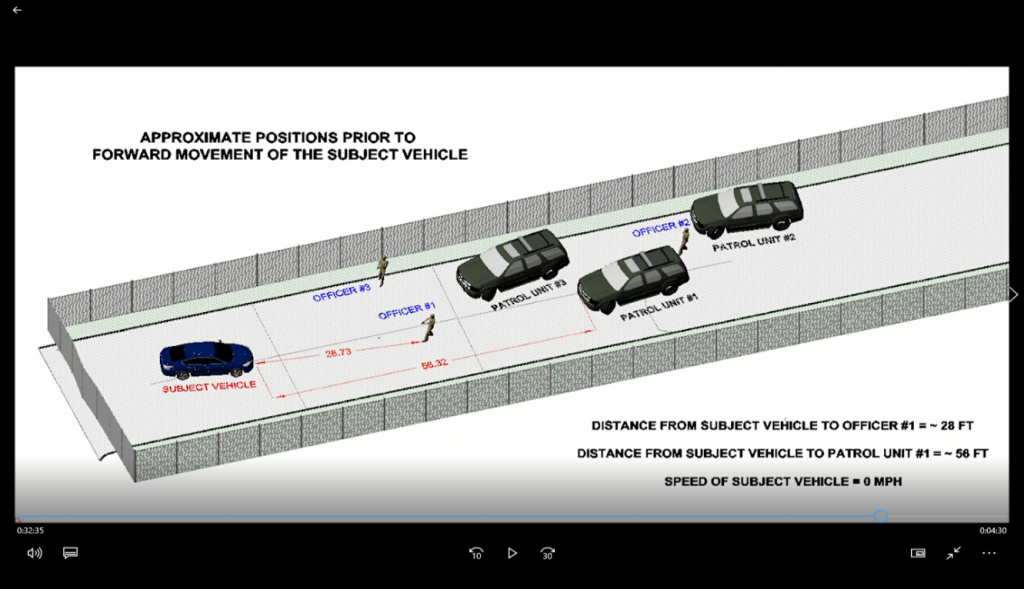

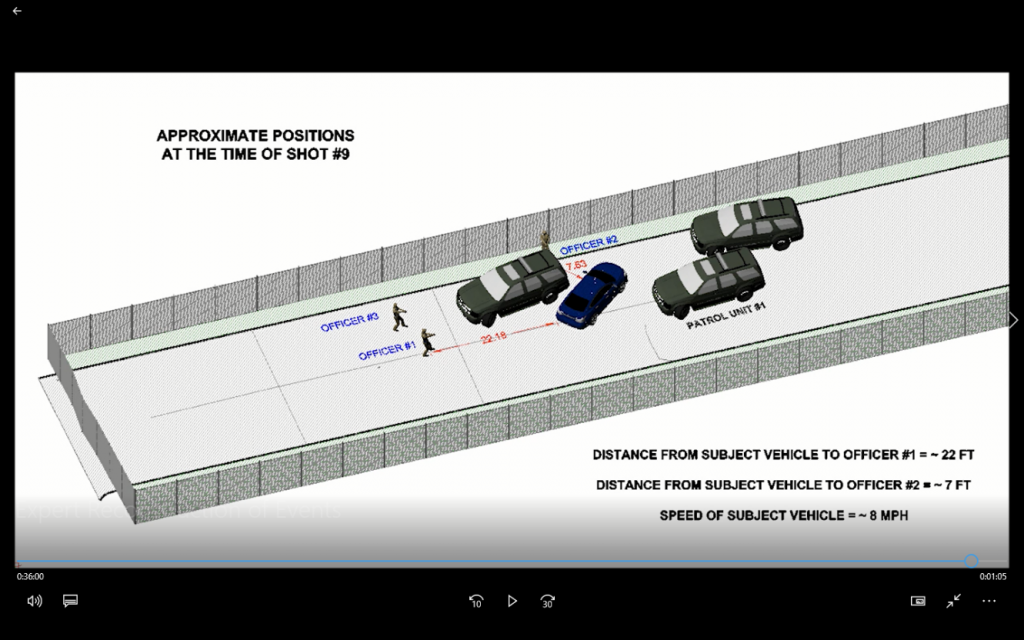

Due to a dead end at Rosemont Avenue, Mr. Moses was in the process of making a U-turn, when the officers caught up to him in their patrol SUVs. Officer Sweeney-Jones pulled up in front and toward the right side of the road; with Officer Ieradi slightly behind him and closer to the middle of the road; and Corporal Ellis in back and toward the right side of the road. See below Diagram 1. As Mr. Moses backed up his car, all three officers left their patrol SUVs and started walking toward his car with their guns drawn.9 Officer Ieradi and Officer Sweeney-Jones shouted commands telling Moses to “Stop the fucking car” and “Don’t do it.” Based on our review of the bodycam footage, 10 seconds after Officer Ieradi and Officer Sweeney-Jones began shouting these commands, Mr. Moses hit the accelerator (with an engine RPM of approximately 2,00010) and drove his car forward toward the officers and their patrol SUVs, but veered to Officer Ieradi’s left, presumably in an effort to get around him and escape. Compare Diagram 1 with Diagram 2.

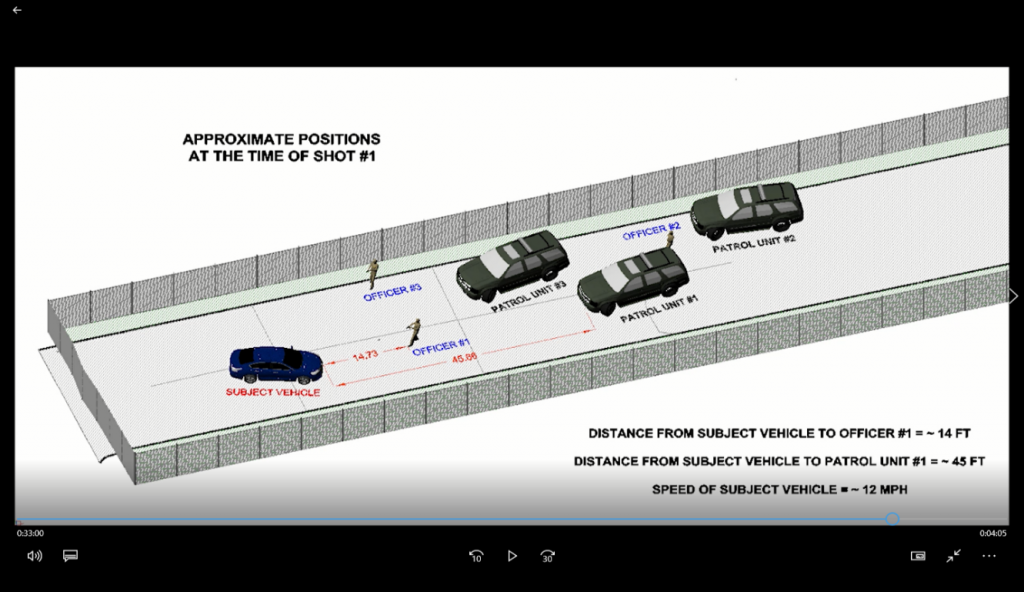

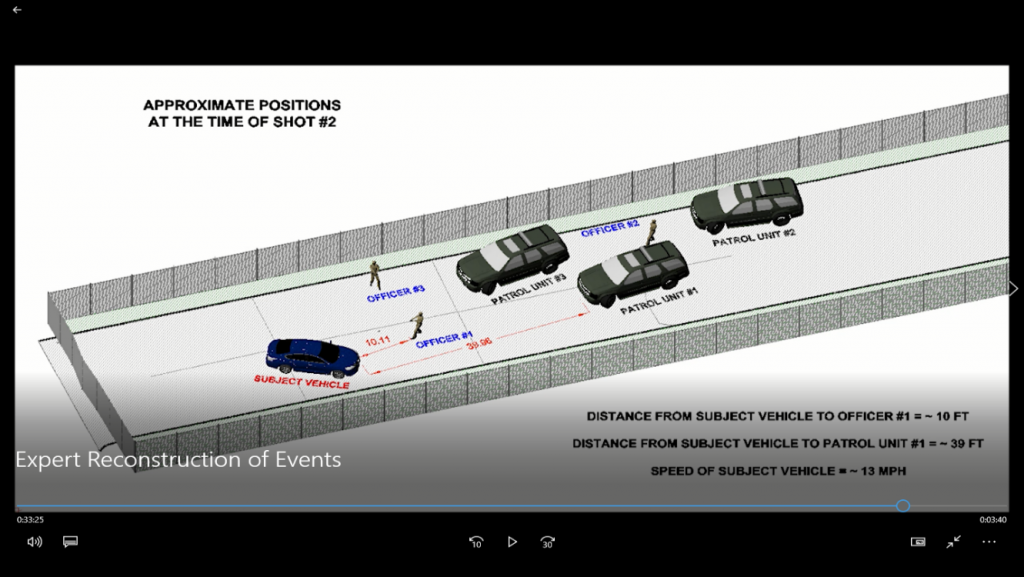

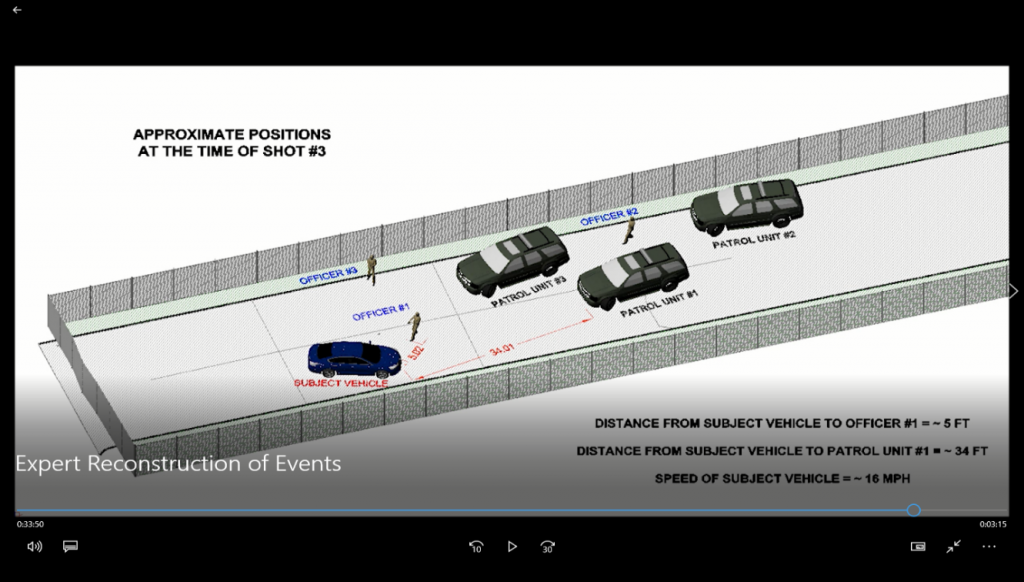

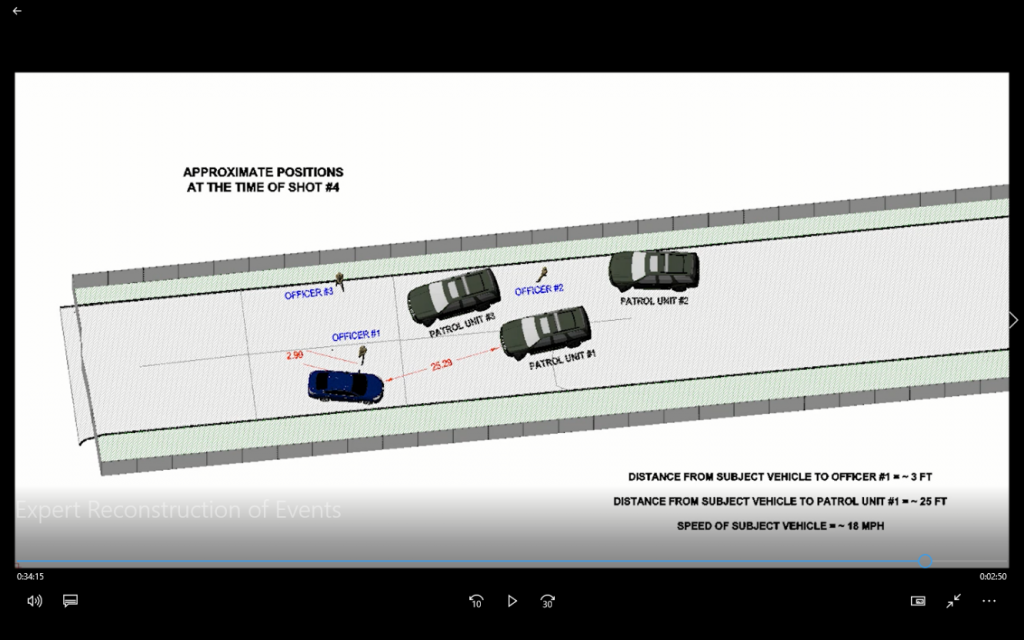

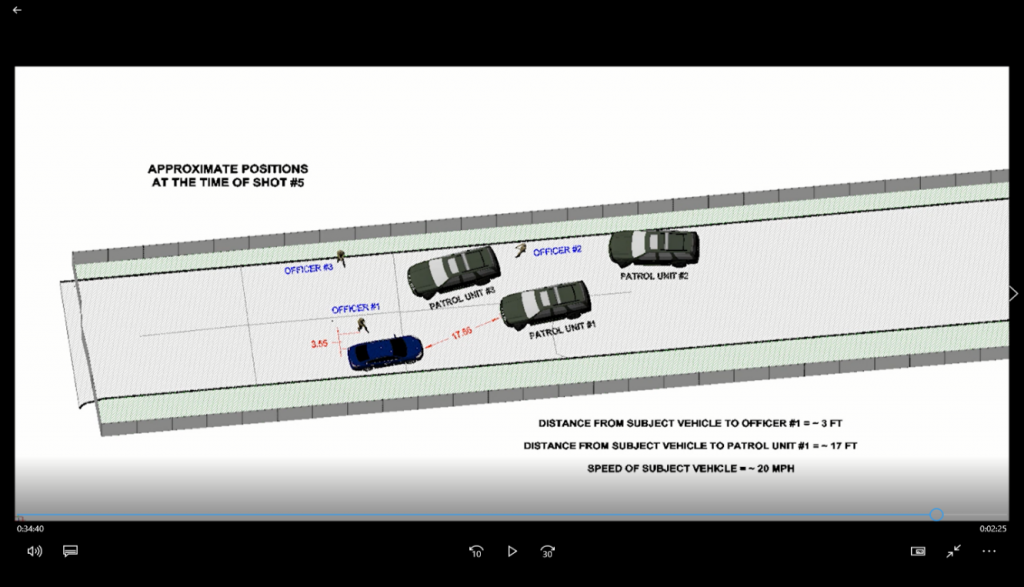

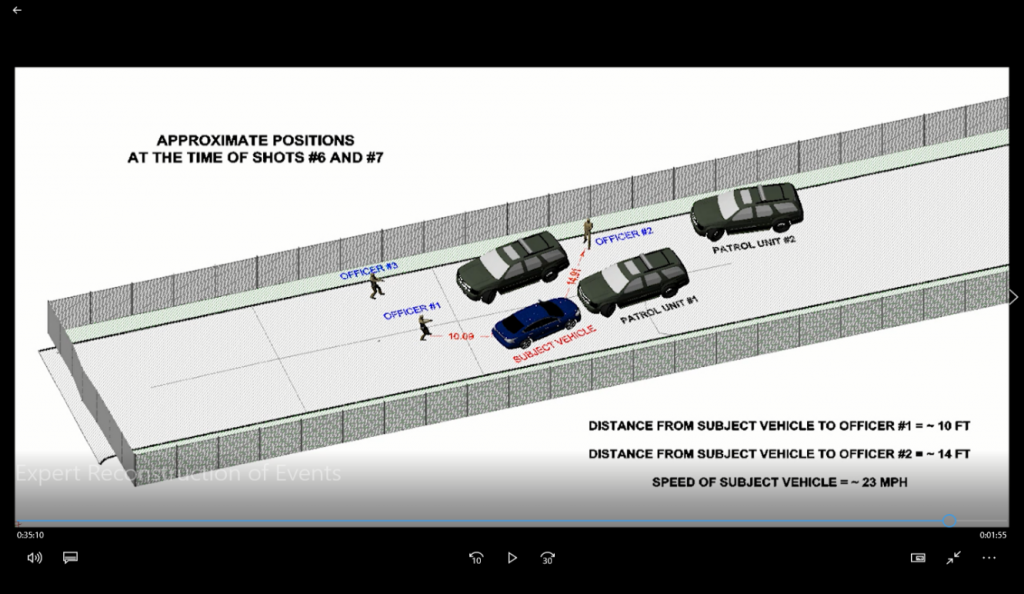

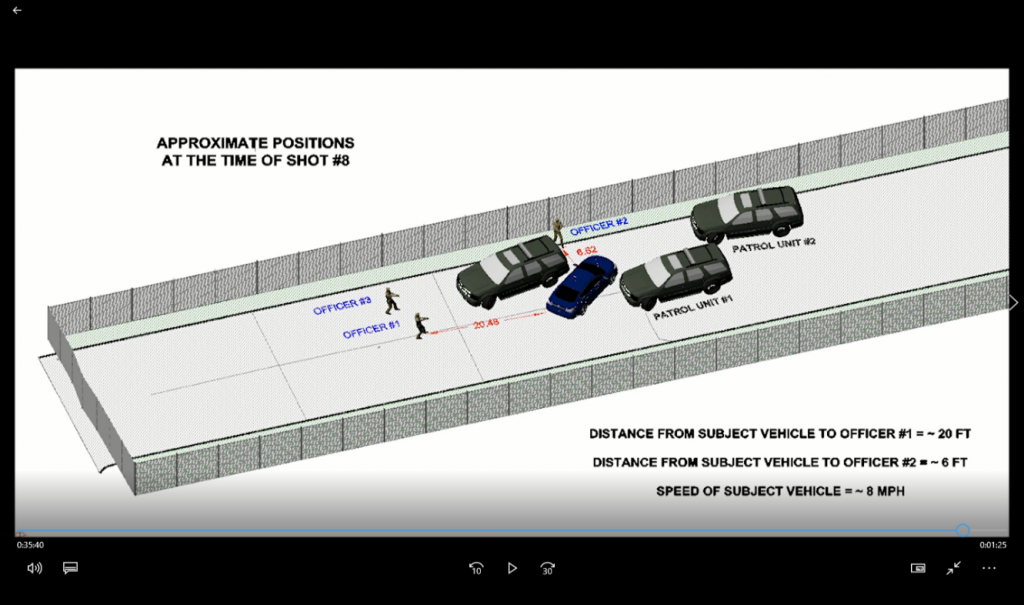

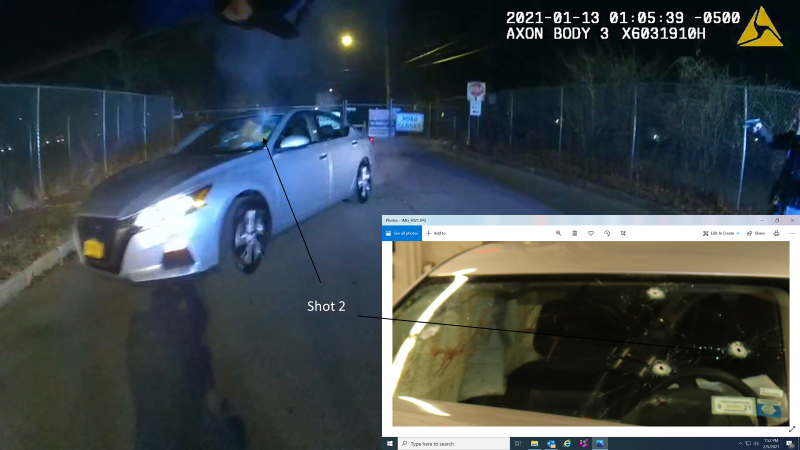

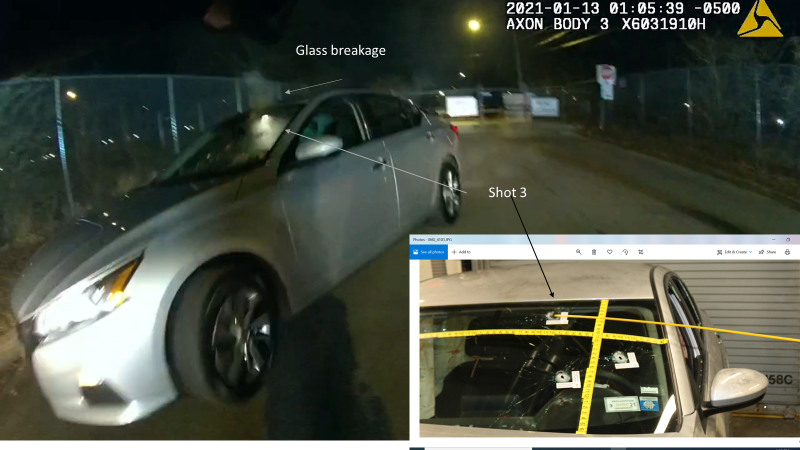

Officer Ieradi fired seven shots at Mr. Moses’s vehicle: three into the windshield when the car was coming toward him and steering around him, see Diagrams 2–4; two shots into the left side of Mr. Moses’s car (including through the driver’s window) as the vehicle passed him, see Diagrams 5–6; and two toward the back of Mr. Moses’s car as Mr. Moses lost control of his car and veered toward the patrol SUVs and Corporal Ellis, see Diagram 7. Corporal Ellis shot twice as the vehicle veered in his direction. See Diagrams 8–9. Mr. Moses’s vehicle crashed into Officer Ieradi’s patrol SUV and then came to a halt. Officer Ieradi ultimately pulled Mr. Moses out of his vehicle and attempted to render aid. Mr. Moses was pronounced deceased by New Castle County Emergency Medical Service at 1:25 a.m.

Diagrams from Expert Critical Incident Review (CIR)

According to the March 22, 2021 autopsy report, Mr. Moses’s cause of death was a gunshot wound to the left side of his head at an indeterminate range. A bullet was recovered from his brain stem, believed to be connected to Officer Ieradi’s fourth shot through the driver’s window of Mr. Moses’s vehicle.

The New Castle County Police Department investigated and submitted its findings to the Delaware Department of Justice on July 13, 2021. During the course of their investigation Sergeant Michael Bradshaw and Sergeant Reginald Laster interviewed Officer Ieradi (on January 29, 2021), Corporal Ellis (on January 18, 2021), and Officer Sweeney-Jones (on January 13, 2021) in the presence of their respective legal counsel. All three were permitted to view the bodycam footage of the incident before their respective interviews, and none were questioned on their use of force training or whether their conduct that night complied with how they had been trained.

Officer Ieradi indicated during his interview that he discharged his weapon because he believed that Mr. Moses’s vehicle would hit either him or Corporal Ellis (whom he mistakenly referred to as Officer Sweeney-Jones) and he wanted to stop the vehicle. He admitted that he could not see from his vantage point where Corporal Ellis was located, but he believed him to be in the path of Mr. Moses’s car behind Officer Ieradi. The lack of communication between the officers as they pursued Mr. Moses’s car and then left their SUVs likely contributed to Officer Ieradi’s inability to assess Corporal Ellis’s location. Corporal Ellis indicated he discharged his weapon because he feared that the vehicle was going to hit him, killing him or causing serious injuries, since he was in a “fatal funnel” caused by the location of the two patrol SUVs around him. See Diagrams 7–9.

In both the report submitted to the Delaware Department of Justice and a critical incident briefing provided to the public on March 16, 2021, the New Castle County Police Department provided significant detail on Mr. Moses’s criminal history and character, despite the fact that none of these details were available to the Officers on January 13, and could not have informed their decision to use deadly force, and thus was legally insignificant insofar as an evaluation of the officer’s conduct is concerned and to any determination of whether deadly force was warranted. We believe that the Police Department’s choice to focus on the irrelevant details of Mr. Moses’s prior criminal history served to both (1) undermine an ongoing criminal investigation by prejudicing public opinion and (2) detract from the public’s ability to trust the integrity of the Police Department’s investigation of the shooting. By focusing its statements on Mr. Moses’s prior criminal conduct—which was unknown to any of the officers involved in the shooting—the Police Department was seemingly attempting to justify the shooting to the public based on its perception of the character of the victim instead of based on the tragic facts and circumstances that led to the shooting. The Police Department’s attempt to devalue the life of Mr. Moses surely angered and disgusted many in the community and engendered greater skepticism of the good-faith nature of the investigation.

Legal Analysis

After reviewing these facts from the New Castle County Police Department’s and Department of Justice’s investigations, Morgan Lewis considered whether criminal charges could justifiably be brought against any of the three officers at the scene. As Officer Ieradi discharged his weapon first, and his fourth shot was determined to likely be the cause of death, our primary focus was on his conduct and decision to begin firing at Mr. Moses.12

Applicable Justification Statutes: Use of Deadly Force for Self-Protection or Protection of Others

The State must determine whether the use of deadly force by New Castle County Police Department officers constitutes a criminal act based on the Delaware Criminal Code as it existed at the time of the shooting. Officer Ieradi’s and Corporal Ellis’s actions would constitute use of deadly force under the Criminal Code because “[p]urposely firing a firearm in the direction of another person or at a vehicle in which another person is believed to be constitutes deadly force.” 11 Del. C. § 471. While the reckless use of deadly force resulting in an individual’s death can trigger a homicide charge such as manslaughter, there are three justification defenses available to a police officer when facing criminal charges. In a criminal case, the State must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that an officer’s use of deadly force was not justified either for self-protection (11 Del. C. § 464), the protection of other persons (11 Del. C. § 465), or for a permissible law enforcement purpose (11 Del. C. § 467). As the Department of Justice has commented in previous incident reports, the Delaware Criminal Code’s treatment of these three justifications grants law enforcement significant deference regarding the use of deadly force. In fact, under the Code there are only a limited set of circumstances where one can question the reasonableness of an officer’s use of deadly force based on these justifications.13

The first defense available to a police officer is that use of deadly force was justified for self-protection. 11 Del. C. § 464. It states, “The use of deadly force is justifiable under this section if the defendant believes that such force is necessary to protect the defendant against death, serious physical injury, kidnapping or sexual intercourse compelled by force or threat.” 11 Del. C. § 464(c) (emphasis added). This provision is also available to civilian defendants; however, in the case of law enforcement officer defendants, they are afforded greater deference. While the use of deadly force for self-protection justification is not available for civilians if the “defendant knows that the necessity of using deadly force can be avoided with complete safety by retreating,” a law enforcement officer does not have this same duty to retreat. 11 Del. C. § 464(e)(2), (e)(2)(c).14

The second defense available to a police officer is that use of deadly force was justified for the protection of other persons. This justification reads:

(a) The use of force upon or toward the person of another is justifiable to protect a third person when:

(1) The defendant would have been justified under § 464 of this title in using such force to protect the defendant against the injury the defendant believes to be threatened to the person whom the defendant seeks to protect; and

(2) Under the circumstances as the defendant believes them to be, the person whom the defendant seeks to protect would have been justified in using such protective force; and

(3) The defendant believes that intervention is necessary for the protection of the other person.

11 Del. C. § 465(a) (emphasis added). Like Section 464, this section is also available to civilian defendants.

Both the operative versions of 464 and 465 require only a subjective showing that the officer believed such deadly force was necessary—in order to successfully assert these defenses, the officer need not establish that the use of deadly force was actually necessary to protect the officer or others against death or serious physical injury. While Delaware has since amended these justification statutes to require that such belief be reasonable, these amendments were not effective until June 30, 2021, six months after this incident took place. As a result, under applicable Delaware law, Officer Ieradi and Corporal Ellis are entitled to the legal defense of justification if the evidence supports their subjective belief that their use of deadly force was necessary under the circumstances to protect themselves and/or others. As long as Officer Ieradi or Corporal Ellis could point to credible evidence that they believed such force was necessary under the circumstances (in this case, a car being driven toward them in their immediate direction) to protective themselves and/or others, they would be entitled to a “jury instruction that the jury must acquit the defendant if they find that the evidence raises a reasonable doubt as to the defendant’s guilt.” 11 Del. C. § 303(c). The reality of these justification statutes is that they provide a great deal of deference to police officers regarding the use of deadly force. For these reasons, criminal prosecution of a police officer for responding to a perceived threat with the use of deadly force under the operative Delaware law is extremely challenging.

The only exception to the subjective belief test for Rules 464 and 465 is 11 Del. C. § 470(a):

When the defendant believes that the use of force upon or toward the person of another is necessary for any of the purposes for which such relief would establish a justification under §§ 462-468 of this title but the defendant is reckless or negligent in having such belief or in acquiring or failing to acquire any knowledge or belief which is material to the justifiability of the use of force, the justification afforded by those sections is unavailable in a prosecution for an offense for which recklessness or negligence suffices to establish culpability.

Accordingly, if Officer Ieradi or Corporal Ellis had a belief that deadly force was necessary to protect himself or another against death or serious physical injury, but recklessly or negligently came to that belief, he is not entitled to the subjective belief test outlined in Sections 464 and 465, and his use of deadly force can be reviewed to determine if it was reckless. Recklessly is defined as: “A person acts recklessly with respect to an element of an offense when the person is aware of and consciously disregards a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the element exists or will result from the conduct. The risk must be of such a nature and degree that disregard thereof constitutes a gross deviation from the standard of conduct that a reasonable person would observe in the situation.” 11 Del. C. § 231(e).

Under this framework, to successfully prosecute Officer Ieradi or Corporal Ellis for the use of deadly force against Mr. Moses, the State would need to prove two things:

- That Officer Ieradi and/or Corporal Ellis were/was aware of and consciously disregarded a substantial and unjustifiable risk in obtaining or failing to obtain information he needed to make a determination regarding the use of deadly force, and that the officer’s disregard of the risk constituted a gross deviation from the standard of conduct that a reasonable officer would observe in the situation; and

- That the officer’s decision to use deadly force itself also involved a conscious disregard of a substantial and unjustifiable risk, such that the disregard constituted a gross deviation from the standard of conduct that a reasonable officer would observe in the situation.

Legal Conclusions with Respect to Officer Ieradi and Corporal Ellis

While we believe this incident could have ended differently if the officers had made different choices in how they handled this situation such that there was no shooting or death, the law recognizes that police officers often must make decisions quickly based on the information available under the circumstances and that officers are permitted to use deadly force if they have a reasonable belief that such force is needed to protect themselves or others against death or serious physical injury. The investigative findings show that Officer Ieradi and Corporal Ellis discharged their weapons at Mr. Moses’s vehicle at a time when they believed that doing so was necessary to protect themselves or others against death or serious physical injury.

After Mr. Moses disregarded the officers’ initial orders to step out of his vehicle, he fled the location in his vehicle and the Officers pursued Mr. Moses to the dead end in their vehicles. Officer Ieradi, Corporal Ellis, and Officer Sweeney-Jones exited their patrol SUVs with their guns drawn and again attempted to get Mr. Moses to stop and get out of his car. Officer Ieradi moved away from his patrol SUV and situated himself approximately 28 feet in front of Mr. Moses’s car. After Officer Ieradi again repeated his commands for Mr. Moses to stop his vehicle and get out of the car, Mr. Moses’s vehicle began to move in his direction. While arguments could be made that Mr. Moses’s vehicle was angled to the left of Officer Ieradi, and Mr. Moses was attempting to maneuver around Officer Ieradi, the bodycam footage and expert diagrams based on measurements at the scene reflect that Mr. Moses’s vehicle came quite close to Officer Ieradi. In all the instances detailed below, Officers Ieradi and Ellis were viewing Mr. Moses’s vehicle in the dark with the headlights shining on them.

- The vehicle was approximately 28 feet away from Officer Ieradi before it began moving forward. From this position, four seconds passed before Mr. Moses began driving forward.

- The vehicle was approximately 14 feet from Officer Ieradi traveling at 12 miles per hour when Officer Ieradi fired his first shot through Mr. Moses’s windshield within a second of Mr. Moses’s vehicle moving forward.

- The vehicle was approximately 10 feet from Officer Ieradi traveling at 13 miles per hour when Officer Ieradi fired his second shot through Mr. Moses’s windshield less than a second after his first shot.

- The vehicle was approximately five feet from Officer Ieradi traveling at 16 miles per hour when Officer Ieradi fired his third shot through Mr. Moses’s windshield less than a second after his second shot.

- The vehicle was approximately three feet from Officer Ieradi traveling at 18 miles per hour when Officer Ieradi fired his fourth shot through Mr. Moses’s driver window, as the vehicle passed alongside him less than a second after his third shot.

- The vehicle was approximately three feet from Officer Ieradi traveling at 20 miles per hour when Officer Ieradi fired his fifth shot at Mr. Moses’s vehicle, as the vehicle passed alongside him less than a second after his fourth shot.

- The vehicle was approximately 10 feet from him traveling at 23 miles per hour, quickly veering closer to his patrol SUV and Corporal Ellis when Officer Ieradi fired his sixth and seventh shots at Mr. Moses’s vehicle less than a second after his fifth shot.

- The vehicle was approximately six feet from Corporal Ellis and had swerved in his direction, hitting the patrol vehicles, when Corporal Ellis fired his first shot at Mr. Moses’s vehicle less than a second after Officer Ieradi’s sixth and seventh shots.

- The vehicle was approximately seven feet from Corporal Ellis and had swerved in his direction, hitting the patrol vehicles, when Corporal Ellis fired his second shot at Mr. Moses’s vehicle less than a second after his first shot.

The relatively short period during which these events unfolded (all the events described above from the Officers’ initial pursuit of Mr. Moses’s vehicle to the shots being fired occurred within one minute), combined with how quickly the event escalated once Mr. Moses’s vehicle was pursued (only 10 seconds passed between when the officers left their vehicles shouting commands and when Mr. Moses hit the accelerator), suggest that the officers did not have time to do a rational analysis of how far the vehicle was away from them, how fast it was coming, and what precise direction it was headed. Within the same second Mr. Moses hit the gas, Officer Ieradi began shooting at Mr. Moses’s vehicle; all of the shots (both Officer Ieradi’s and Corporal Ellis’s) were fired over the next four seconds. While it became clear by Officer Ieradi’s fourth shot that Mr. Moses’s vehicle was not going to hit him, the bodycam footage demonstrates that Officer Ieradi could not see Corporal Ellis’s location. As a result, there is nothing to negate Officer Ieradi’s argument that he thought Corporal Ellis could be in the path of the car and therefore in danger.15

During his interview, Officer Ieradi explained that when Mr. Moses’s vehicle started moving forward, he heard the tires screech, believed that the vehicle was coming toward him, believed that an officer was directly behind him and that the vehicle was going to strike either one of them in order to pass. As a result, Officer Ieradi began firing his gun at the vehicle with the intention of stopping the vehicle before it hit him or his fellow officer, as he tried to get out of the vehicle’s path. He also stated that he did not believe there was a path for the vehicle to pass without striking an officer or patrol SUV. Finally, Officer Ieradi stated that based on how agitated Mr. Moses was when they initially approached his vehicle (sweating profusely, out of breath, and clenching his fists) he thought there was a chance that Mr. Moses was under the influence of a substance that was affecting his decision-making and behavior.

Regarding Corporal Ellis’s decision to discharge his firearm, Corporal Ellis made a statement that he fired his gun after the car turned and started heading toward him because he was in fear that the vehicle was going to hit him, killing him or causing serious injuries, since he was in a “fatal funnel” caused by the location of the two patrol SUVs around him.

Both Officer Ieradi’s and Corporal Ellis’s statements, regarding the path of Mr. Moses’s vehicle, concern for their safety or the safety of their fellow officers, and Mr. Moses’s previously agitated behavior corroborate their justifications that they discharged their firearms because they believed it was necessary to prevent death or serious injury to themselves or others, consistent with Sections 464 and 465. Their statements were generally corroborated by the bodycam footage.

To address whether Officer Ieradi’s or Corporal Ellis’s actions fall within the exception to these two justifications, specifically, whether they were reckless in acquiring or failing to acquire information needed to form their belief about the need to protect themselves, the State must look to the use of force training these officers received. Based on this use of force training, the State must determine whether these officers were aware of a substantial and justifiable risk in making a determination regarding the use of deadly force under these circumstances and whether disregard of this risk was a gross deviation from the standard of conduct.

Based on a review of New Castle County Police Department’s policies on use of deadly force, as well as the training that the department provided to their officers, we believe the State will be unable to show that Officer Ieradi and Corporal Ellis acted recklessly in reaching the conclusion that use of deadly force was necessary to prevent death or serious injury to themselves or others.

The New Castle County Police Department’s use of force policy does have an applicable restriction against discharging a weapon at a moving vehicle:

Officers are prohibited from discharging their firearm in the following instances: . . . 2. At a motor vehicle and/or the occupants therein, unless as a last resort and only when the operator of the vehicle is directing the vehicle as deadly force against the officer or other innocent persons and the officer believes employing deadly force creates no substantial risk of injury to innocent persons. Officers should make every effort to not place themselves in the path of a moving vehicle.

New Castle County Police: Use of Force Policy – Directive 1 (Appendix 1-A), Section VI.D (2) (emphasis added). When considering this policy alongside Officer Ieradi’s actions, Officer Ieradi may not be in complete compliance with this policy, in that he did not take every effort to not place himself in the path of a moving vehicle. On the other hand, the policy provides a large carve-out for officers to shoot at a moving vehicle when that vehicle is being used as an instrument of deadly force. This inserts a level of flexibility and officer discretion in the policy that Officer Ieradi and Corporal Ellis can rely on in arguing that they did not act recklessly and counter to the Department’s policy.

Furthermore, even if an argument could be made that Officer Ieradi violated this policy, the State would have difficulty establishing that Officer Ieradi was properly trained on this policy. Despite the fact that the New Castle County Police records provided to DCRPT show that this policy has been in place since at least August 2017, it appears none of the use of force training developed and presented by the Department to its officers ever covered this policy. In fact, just a month before the January 13, 2021 incident, New Castle County police officers received a training course titled “2020 Control Tactics Legal Update and Use of Force In-Service”16 that not only fails to mention this policy, but appears to directly contradict the spirit of this policy.

In this December 22, 2020 training, the slides and speaker notes suggest that the presenter was critical of county policies and national template policies that restrict shooting at moving vehicles. The presenter may have first criticized National Consensus Policies in general, noting these organizations tend to be more restrictive: “[T]his [National Consensus] policy emphasizes that officers have to exhaust all other means prior to the use of deadly force in some instances, which the IAP has been fighting for years now, and also forces the officer to determine the intent of the assailant prior to using the deadly force.” Based on the speaker notes, the presenter then showed a National Consensus policy restricting shooting at moving vehicle and commented:

So in this slide it will show National Consensus policy restrictions and how it applies in a case where an undercover ofc. in an unmarked vehicle was nearly run over by a fleeing suspect wanted for multiple robberies. Now we know through the 4th amendment there are no requirements to exhaust all means prior to the reasonable use of deadly force. And that there is no duty to retreat. This shifts the analysis of the use of force by the officer to the perspective of the intent of the individual. It makes the officer decide whether the individual is just trying to get a way [sic] or run him over. The 4th Amendment clearly states in Graham v. Conner that it is from the perspective of the officer with how the analysis must occur.

The significance of this training is that rather than train the officers on the New Castle County Police Department’s specific policy restricting shooting at a moving vehicle, the instructor decided instead to criticize a template policy that mirrors the county policy.17

Although Officer Ieradi and Corporal Ellis may have been required to read and follow the Department’s use of force policy restricting shooting at moving vehicles, it appears that they were never specifically trained on this policy and may have received training contrary to this policy within a month of the incident. As a result, the State will likely not be able to show that Officer Ieradi and Corporal Ellis recklessly or negligently reached a belief that this type of deadly force was necessary (and permissible) to prevent death or serious injury to themselves or others. Given the evidence outlined above, there is no evidence to suggest that Officer Ieradi and Corporal Ellis did not have a sincere belief that the car presented a serious danger to themselves or other officers. Based on its review of the investigation, Morgan Lewis believes that the Department of Justice cannot successfully prosecute criminal charges against Officer Ieradi or Corporal Ellis, and that it cannot properly or ethically initiate such charges when it does not believe that there is a reasonable probability of conviction.

Policy Recommendations 18

Mr. Moses’s untimely death from a police encounter raises broader questions on use of force tactics, specifically what force can and should be used against moving vehicles. Policymakers, advocacy groups, and law enforcement experts have commented that shooting at moving vehicles is a dangerous and ineffective tactic.19 This tactic is viewed as ineffective for stopping oncoming vehicles and presents overwhelming risks to innocent parties. In these circumstances, Officer Ieradi’s shots at Mr. Moses’s vehicle not only killed Mr. Moses, but arguably put his fellow officer in harm’s way. Mr. Moses’s vehicle did not veer toward Corporal Ellis until Mr. Moses was shot in the head, disabling him and causing him to lose control of the vehicle.

Accordingly, as the Delaware Department of Justice continues its work with 21CP to address the need for reviewing and reforming Delaware law enforcement agencies policies and use of force training, we recommend that the Department of Justice consider the following:

Recommendation 1: Advocate for law enforcement policies that restrict shooting at moving vehicles. While we understand that the New Castle County Police Department already has a policy restricting shooting at moving vehicles, the existing policy provides a level of flexibility and officer discretion that reduces the effectiveness of this policy. Research has shown that broader restrictions on this ineffective and dangerous policing tactic—with limited and clear justification caveats—are more effective in protecting police officers and the community at large. In line with comparative policies in other jurisdictions we recommend that such policies include:

- An explanation on why the tactic is condemned, including descriptions on how dangerous the tactic is and why it is not effective.20

- Modifications to any exceptions to the restriction so that a moving vehicle alone cannot be viewed as a deadly instrument justifying shooting at the vehicle.21

- Duty for officers to avoid placing themselves in the path of a moving vehicle and to affirmatively make efforts to move out of the path of a moving vehicle.22

- Warning that an officer cannot rely on the exception to this restriction.23

- Allow exception to the restrictions for responding to vehicle ramming attacks: when a perpetrator deliberately rams, or attempts to ram, a motor vehicle at a crowd of people with the intent to inflict fatal injuries.24

- Allow exception to the restrictions for responding to mass casualty terrorist events.25

Recommendation 2: Advocate for changes in Use of Force and Firearms trainings employed by the New Castle County Police Department, and other law enforcement agencies. In reviewing New Castle County Police Department’s Use of Force trainings over the years, we were concerned to see that the trainings were not focused on teaching officers what are appropriate and inappropriate uses of force and on educating officers on the Department’s policies, but instead on providing law officers with the least restrictive constitutional framework on use of force so they understood their legal risk and potential liability. While we recognize that it is important for officers to understand how improper use of force tactics can result in both personal and departmental liability, the trainings conducted by the Department should be geared toward what actions the Department policy actually limits and restricts. The constitutional framework is merely a floor for determining what use of force will trigger liability, it does not reflect the best practices that have developed in policing and that are incorporated into a Department’s more restrictive policies. We believe an approach that focuses on clear restrictions and parameters on the use of force will give officers greater clarity on the tools available to them so they can effectively and safely work in their communities. We believe this can be achieved by advocating for the following changes to use of force trainings:

- Pressing for less of a focus in these trainings on constitutional framework, which fosters ambiguity and confusion, and instead spend more time reviewing the actual restrictions and limitations on use of force in that department;

- Making sure training is consistent with departmental policy and does not contradict the policies;26

- Pushing for the implementation of mechanisms to track whether officers are reading the policies;

- Changing firearms training so it does not encourage “shooting until the problem is solved,” which conflicts with the boundaries of the justification statutes which permit use of deadly force only under a limited amount of circumstances.

Recommendation 3: Advocate for changes in vehicular pursuit and traffic stop trainings that address the poor operational tactics and communication that were employed in this incident. As explained above, the officers at the scene employed questionable communication tactics, in that (1) they gave simultaneous commands to Mr. Moses that likely caused further confusion; (2) did not communicate with each other during the vehicular pursuit to share information on the road conditions and strategy for the pursuit and reengagement. Moreover, we believe this police department—and perhaps other departments in Delaware—would benefit from guidance from 21CP on the strategic placement of SUVs, when to leave one’s SUV when blocking a moving vehicle, and when to seek the support of additional officers. We understand that 21CP has expertise in this area that can inform implementation of this recommendation.

Recommendation 4: Consider working with an independent agency to conduct use of force training and investigate police-involved shootings. Regarding use of force trainings, working with an independent agency may help ensure that there are equivalent levels of use of force training throughout the state, while ensuring that the training still considers local variations to any policies. Regarding working with an independent agency to investigate police-involved shootings, such involvement will both strengthen the rigor of these investigations, instill public trust in these investigations, and confidence for law enforcement departments that an independent third party has assessed and stands by the Department’s appropriate uses of force. Our review of the New Castle County Police Department’s investigation into the shooting incident raised significant questions on both the rigor of the Department’s investigation and the perception it gave to the public when it made statements intimating that Mr. Moses’s death was not worth paying attention to given his criminal history (a history the officers were not aware of at the time they encountered him). The interviews were not adversarial and steered away from difficult but important questions on the officers’ understanding of their use of force training, impressions on how their actions conflicted with the training, lack of communication among themselves during the vehicle pursuit despite unfamiliarity with the area, decisions to place themselves in the path of a moving vehicle, and failure to account for the location of their fellow officers. Without a rigorous and adversarial investigation, the public loses trust in the investigation process and contributes to a belief that the disposition of these investigations is set at the start. Involvement of an independent agency will also help address a culture prevalent at many law enforcement departments, such as New Castle County Police Department, where officers actively put themselves in harm’s way by unnecessarily escalating situations.

Recommendation 5: Address Inappropriate Department Communications Regarding Pending Criminal Investigations. The Department’s public statement that focused a fair portion on a character assessment of Mr. Moses and review of his criminal background, without regard to whether the officers knew about this background at the time of their encounter, only increased public distrust. Notably, such public statements served no legitimate public interest and also would have prejudiced potential grand jurors and trial jurors had the Department of Justice decided that criminal charges were available and appropriate here. It was a poor investigative tactic and decision on the part of the New Castle County Police Department to introduce to the public information about Mr. Moses that likely would have been inadmissible in any trial against the officers who used deadly force against him. Although criminal charges were not available or appropriate here, public statements such as these undermine the Department of Justice’s role in assessing and prosecuting cases.

While we have determined that criminal charges are not appropriate here as the evidence permits a justification defense and is not reasonably likely to support a conviction, we make these recommendations to encourage Delaware and its law enforcement agencies to use this as an opportunity to address the shortcomings of the New Castle County Police Department’s policies and trainings that contributed to these circumstances. Addressing flawed policies and gaps in these use of force trainings will not only serve to help prevent incidents like this one from happening again, but also will increase the safety of members of law enforcement, and members of the public they serve, thereby increasing the public’s trust in its law enforcement agencies.

1 Zane David Memeger, Nathan J. Andrisani, Nicholas M. Gess, and Caitlin Barrett of Morgan Lewis worked on this matter. Memeger is a former U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania (2010–2016) and served as a prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney’s Office (1995–2006). Andrisani is a former Assistant District Attorney for the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office (1995–1999). Gess is a former U.S. Associate Deputy Attorney General (1994–2001), served as a prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Maine (1986–1994) and as a prosecutor in the Maine Attorney General’s Office (1981–1985). Barrett is a former investigative analyst with the Sex Crimes Unit for the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office (2012–2014).

2 An index of the investigation materials provided to Morgan Lewis is attached hereto as Exhibit 1.

3 A Garrity warning is given to public employees when they are required to provide truthful answers on pain of discipline (including termination), on the condition that those answers may not be used against the employee in subsequent criminal proceedings. Morgan Lewis, like DCRPT prosecutors in other cases, did not review any statements subject to a Garrity warning, to the extent such statements were made, because any such statements would not be admissible in court.

4 As of June 30, 2021, this standard is no longer the law of the State of Delaware. A less deferential, objective standard was codified via Senate Bill 147 after being signed by the Governor.

5 As part of our analysis of Officer Ieradi’s and Corporal Ellis’s decision to draw and fire their weapons at Mr. Moses as he drove his car in their direction, which resulted in the death of Mr. Moses, Morgan Lewis considered the following offenses under the Delaware Criminal Code: (1) homicide offenses requiring a reckless or negligent state of mind (Murder in the Second Degree, Manslaughter, Criminally Negligent Homicide); and (2) reckless endangerment in the first and second degree. In addition, as there was another officer at the scene, Officer Sean Sweeney-Jones, Morgan Lewis evaluated whether his conduct would constitute conspiracy to commit any of the above-listed offenses.

6 See, e.g., Barker et al., “How Police Justify Killing Drivers: The Vehicle Was a Weapon,” The New York Times (Nov. 6, 2021) (“The country’s largest cities, from New York to Los Angeles, have barred officers from shooting at moving vehicles. The U.S. Justice Department has warned against the practice for decades, pressuring police departments to forbid it. Police academies don’t even train recruits how to fire at a car. The risk of injuring innocent people is considered too great; the idea of stopping a car with a bullet is viewed as wishful thinking. . . . Moving vehicles can be deadly. Nine officers have been fatally run over, pinned or dragged by drivers in vehicles approached for minor or nonviolent offenses in the past five years.”).

7 See id.; see also infra notes 19–25.

8 Notably, the three officers were not communicating with one another on the radio during the pursuit to plan out how they were going to proceed with Mr. Moses. From interviews with the three officers after the event, it appeared that only one of the officers knew that Rosemont Avenue ended in a dead end, demonstrating the need for further communication between the three officers.

9 Moreover, most likely due to the lack of communication, Officer Ieradi repeatedly mentioned during his interview that he did not know where Corporal Ellis (who he mistakenly referred to as Officer Sweeney-Jones) was located, so he assumed that Corporal Ellis was immediately behind him or directly in the path of Mr. Moses’s vehicle.

10 See Robert Bosch LLC Crash Data Retrieval Report for 2020 Nissan Altima (Jan. 15, 2021).

11 See New Castle County Police Department Master Supplement Report (Case No. 32-21-003169) at 43.

12 Although Corporal Ellis discharged his weapon as well, he did so only after hearing Officer Ieradi fire multiple shots and seeing Mr. Moses’s vehicle swerve directly at him, which we recognized would not support an attempted homicide charge. We also determined that Officer Sweeney-Jones’s conduct did not rise to the level of conspiracy to commit any offense.

12 On June 30, 2021, the Delaware Criminal Code was amended to inject an objective standard of “reasonably believes” into these justification statutes. However, because this incident occurred before this amendment was effective, the earlier versions of these justification statutes are the operative ones.

13 11 Del. C. § 464(e)(2)(c) reads: “A public officer justified in using force in the performance of the officer’s duties, or a person justified in using force in assisting an officer or a person justified in using force in making an arrest or preventing an escape, need not desist from efforts to perform the duty or make the arrest or prevent the escape because of resistance or threatened resistance by or on behalf of the person against whom the action is directed.”

14 The fact that Officer Ieradi could not see Corporal Ellis makes it all the more concerning and dangerous that he fired shots at the vehicle after the vehicle passed Officer Ieradi.

15 While the New Castle County Police Department provided a copy of Officer Ieradi’s training log, showing that he attended this in-service, we were not provided with a similar training log for Corporal Ellis.

16 Officers Ieradi and Sweeney-Jones, and Corporal Ellis, were never questioned on their use of force training and asked to explain whether their actions fit into their understanding of the use of force policy. Information on both (1) who provided the training and (2) whether the slide deck and speaker notes conformed with what actually was presented on December 22, 2020 was not readily available. This is again indicative of the concerning gaps in the county’s investigation of this shooting event, and forces us to question whether the County’s Professional Standard Unit has sufficient resources to “analyze use of force reports and prepare a documented annual summary noting any patterns or trends that need to be addressed by policy modifications, training or equipment upgrades” as required by the county’s policies. New Castle County Use of Force Policy – Directive 1, Appendix 1-A, VII. Use of Force Training.

17 While these policy recommendations stem from an incident involving New Castle County Police Department, we suggest that the Delaware Department of Justice consider addressing these recommendations with all Delaware law enforcement agencies.

18 See, e.g., U.S. Department of Justice Community Relations Service, Community Relations Services Toolkit for Policing: Guide to Critical Issues in Policing, https://www.justice.gov/file/1376346/download; International Association of Chiefs of Police, Model Use of Force Policy (2006), IV.B.3, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/2303826-useofforcepolicy.html; Police Executive Research Forum, Guiding Principles on Use of Force at Campaign Zero’s, Principle 8, p. 44 (Mar. 2016), https://www.policeforum.org/assets/guidingprinciples1.pdf; #8CANTWAIT Project, http://www.8cantwait.org.

19 See, e.g., Camden County Police Department, Volume 3, Chapter 2, Use of Force Policy, Section 23 (Rev. 8/21/2019) (“While any firearm discharge entails some risk, discharging a firearm at or from a moving vehicle entails an even greater risk to innocent persons and passengers because of the risk that the fleeing suspect may lose control of the vehicle. Due to this greater risk, and considering that firearms are generally not effective in bringing moving vehicles to a rapid halt, an officer shall not fire from a moving vehicle, or at the driver or occupant of a moving vehicle.”).

20 See, e.g., Baltimore Police Department, Policy 1115: Use of Force, Restrictions on the Use of Deadly Force/Lethal Force Section 6 (Nov. 24, 2019) (“Members shall not fire any weapon from or at a moving vehicle, except: 6.1 To counter an immediate threat of death or Serious Physical Injury to the member or another person, by a person in the vehicle using means other than the vehicle.”); Chicago Police Department, General Order G03-02, Use of Force, Section III.D.5. (Dec. 4, 2020) (restricting the use of firearms “at or into a moving vehicle when the vehicle is the only force used against the sworn member or another person, unless such force is reasonably necessary to prevent death or great bodily harm to the sworn member or to another person”).

22 See, e.g., Philadelphia Police Department, Directive 10.1, Use of Force – Involving the Discharge of Firearms, Section 4(H)(2) (Updated 1/30/2017) (“Officers shall not move into or remain in the path of a moving vehicle. Moving into or remaining in the path of a moving vehicle, whether deliberate or inadvertent, SHALL NOT be justification for discharging a firearm at the vehicle or any of its occupants. An officer in the path of an approaching vehicle shall attempt to move to a position of safety rather than discharging a firearm at the vehicle or any occupants of the vehicle.”).

23 Id.

24 See, e.g., District of Columbia Metropolitan Police, General Order: Use of Force, RAR-901-07 (Nov. 3, 2017) (“Members shall not discharge their firearms either at or from a moving vehicle unless deadly force is being used against the member or another person. For purposes of this order, a moving vehicle is not considered deadly force except when it is reasonable to believe that the moving vehicle is being used to conduct a vehicle ramming attack.”).

25 See, e.g., Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, Procedural Order: Use of Force PO-035-20 (May 15, 2020) (“Officers will not discharge their firearm at a moving vehicle unless: . . . b. The driver is using the vehicle as a weapon to inflict mass causalities [sic] (such as a truck driving through a crowd).”).

26 As outlined above, it appears that the Department never used its use of force trainings as an opportunity to review restrictions on the use of force seen in the local policies, such as the restriction on shooting at a moving vehicle. During the course of our review, we came upon a public statement from Colonel Vaugh M. Bond Jr. to the public. See New Castle County Division of Police: A Comprehensive Look into Our Division, A Message from Colonel Vaughn M. Bond, Jr. Regarding Policing Within Our Communities, https://nccde.org/DocumentCenter/View/38446/FINAL. In this statement, Colonel Vaughn responds to the killing of George Floyd, acknowledges the public outcry, and makes the representation that the new Castle County Police Department is a very progressive agency and is setting the standard for others to follow, and has already aligned its procedures with #8cantwait. He specifically references the ban on shooting at moving vehicles in the policies, saying “the discharging of firearms is prohibited at a motor vehicle and/or its occupants, unless as a last resort and only when the operator is utilizing the vehicle as a deadly weapon.” Such a public statement clearly conflicts with the actual training that was being given to New Castle County’s officers, showing a disconnect between public image and the effective implementation of the Department’s use of force policies.

DCRPT Factual Addendum to Use of Force Report

Civilian Witnesses

Witness 1

Witness 1 was interviewed by investigators and told them that Moses was at their house that night. Moses had a rental vehicle from Enterprise. Sometime between 12:30 A.M. and 1:00 A.M. W1 went out to Moses in the vehicle and found him asleep. W1 gave Moses a juice drink and went back inside. W1 had no further information.

Witness 2

W2 was interviewed by investigators and told them that W2 spoke to Moses around 12:30 A.M. and that he told W2 he was alone and on his way home. W2 provided no further information.

Witness 3

W3 lives in the area of the incident and was interviewed by investigators. W3 stated that they heard the collision and the gunshots. W3 said that Police crashed into Moses vehicle, and then shot him after the crash. W3 said there were approximately 5, 6 or 7 gunshots. W3 was interviewed a second time and said they were in their bedroom when they heard the crash and looked outside and heard police ordering the driver out of the vehicle before shooting him. W3 said they heard nine shots.

Physical Evidence

Shot Spotter

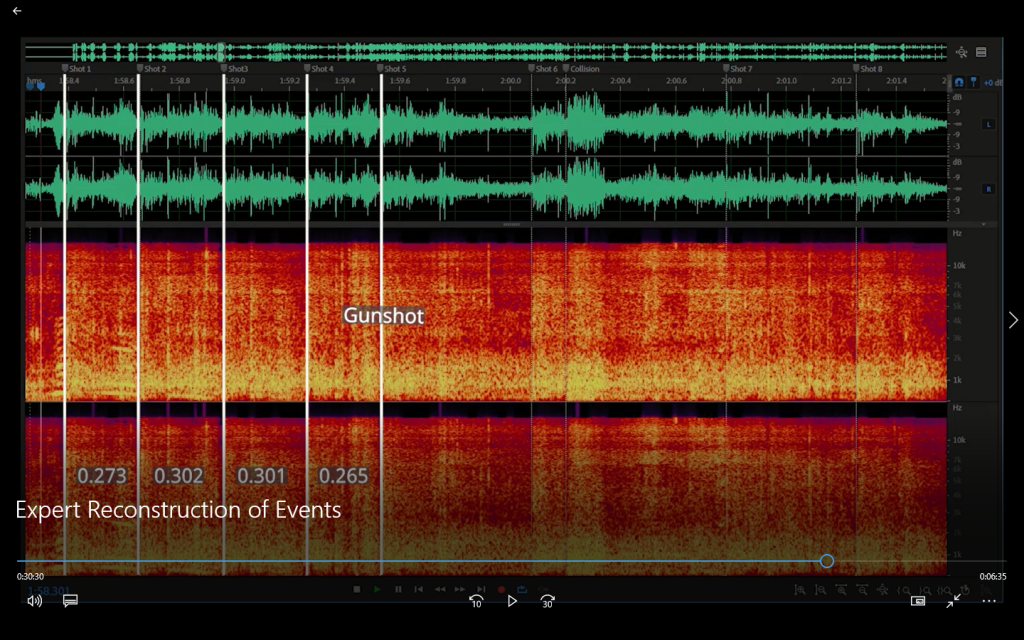

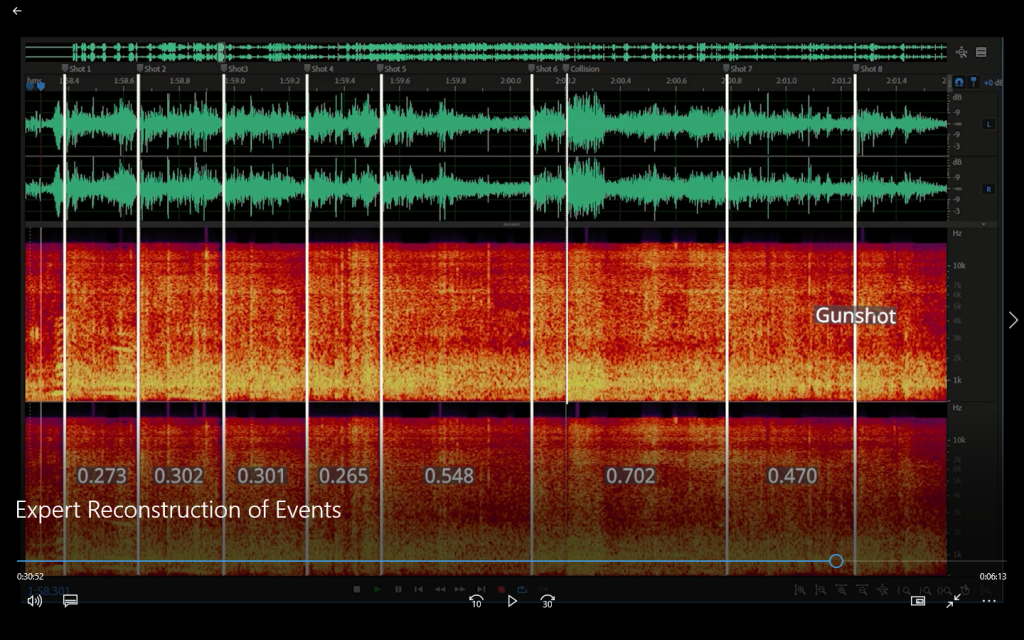

The City of Wilmington Shot Spotter system audibly captured the shots fired by Officer Ieradi and Cpl. Ellis. The alert indicated that seven shots were fired, followed by an additional two shots. The first shot was recorded at 01:05:39.777 hours. The second shot was recorded 0.274 seconds later at 01:05:40.051 hours. The third shot was recorded 0.301 seconds later at 01:05:40.352 hours. The fourth shot was recorded 0.301 seconds later at 01:05:40.653 hours. The fifth shot was recorded 0.269 seconds later at 01:05:40.922 hours. The sixth shot was fired 0.547 seconds later at 01:05:41.469 hours. The seventh, and last shot fired by Officer Ieradi, was recorded 0.708 seconds later at 01:05:42.177 hours.

The first shot fired by Cpl. Ellis was recorded 0.129 seconds after Officer Ieradi’s last shot, at 01:05:42.306 hours. The final shot fired was recorded 0.315 seconds later at 01:05:42.621 hours. According to the Shot Spotter Recording, the total time elapsed from the first shot to the last shot was 2.844 seconds.

Expert Analysis (NCCPD) Audio Stream

The New Castle County Police Dept. hired an independent outside expert (Critical Incident Review) who conducted several analyses of the incident. One of the analyses was the audio stream of gunfire. The follow is a synopsis:

Officer Ieradi

- 1st Shot 0.000

- 2nd shot 0.273

- 3rd shot 0.301

- 4th shot 0.265 (Fatal Shot)

= 0.839 seconds

- 5th shot 0.548

- 6th shot 0.702

- 7th shot 0.470

Cpl. Ellis’ two shots came after all seven of Officer Ieradi’s shots and did not strike Moses (or any third-parties). Therefore, Cpl. Ellis’ two gunshots are also irrelevant to causation.

Medical Report

The autopsy of Moses revealed he died from a single gunshot wound to the left side of his head. A bullet was recovered from the anterior surface of the brain stem. The entrance of the bullet was determined to be the left temporal region of the head, approximately 5 cm above the left external ear canal, and approximately 9 cm below the top of the head.

The toxicology report revealed that Moses was positive for Fentanyl (360 ng/mL), Norfentanyl (52 ng/mL), and Diphenhydramine which is an antihistamine. In a supplemental letter explaining the Fentanyl levels recorded in Moses, Dr. Collins explained that the amount was lethal and “much higher” than levels seen in other deaths. Additionally, the Norfentanyl found is a metabolite of Fentanyl, indicating Moses’ body was breaking down the Fentanyl prior to death and the Fentanyl was recently ingested.

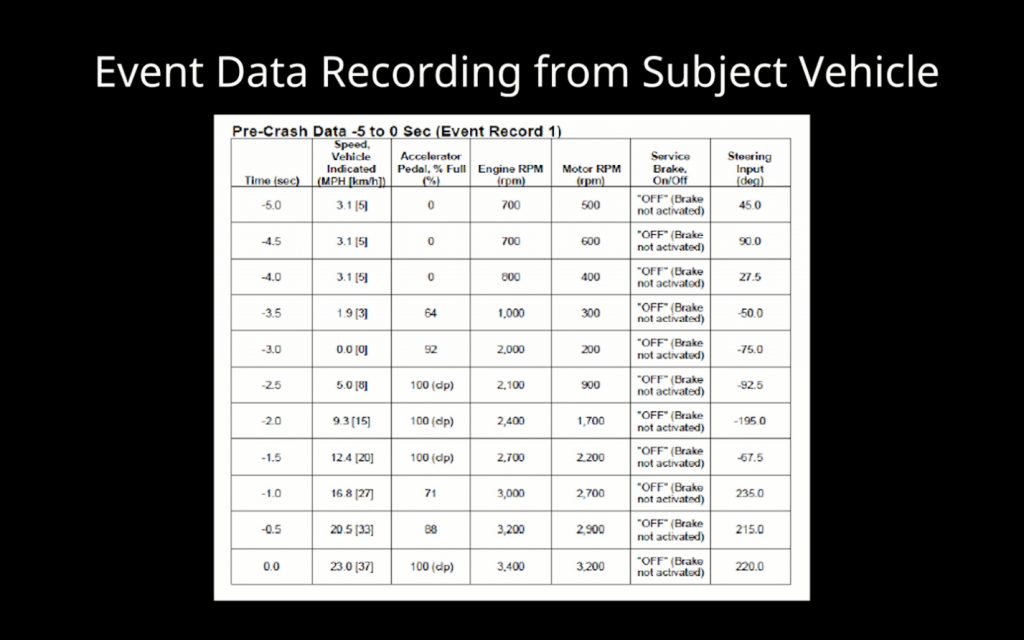

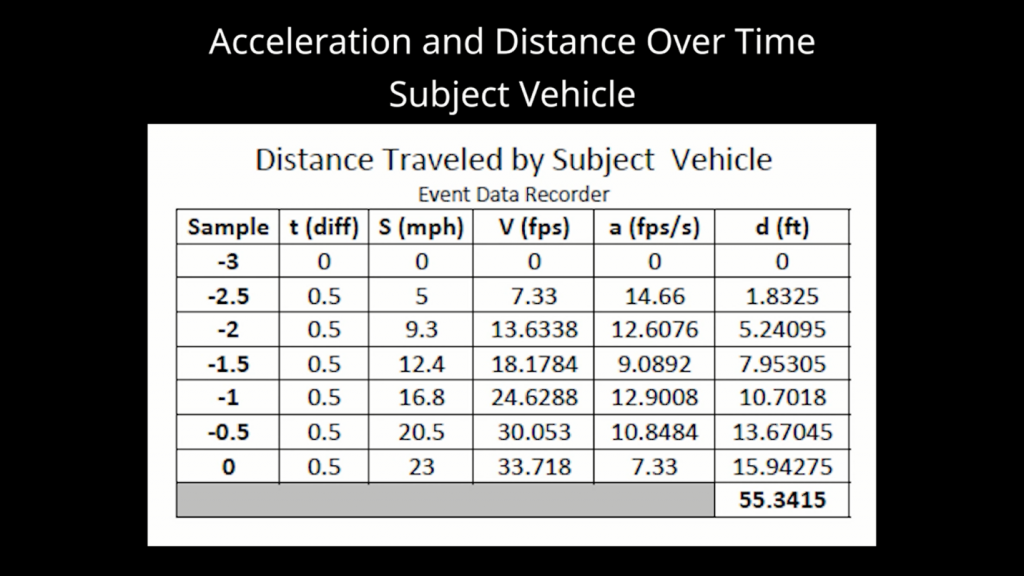

Vehicle Data Downloads

Downloads from all the vehicle’s data were obtained through a Crash Data Retrieval program by BOSCH, for Moses’ rental 2021 Nissan Altima CDRX.

The data includes 5 seconds of Pre-Crash information that is provided in .5 second increments. The report shows that 5 seconds prior to the crash event, the Nissan Altima was traveling 3.1 MPH. The speed being reported is measured by wheel speed. The speed shows speed of 3.1 MPH at -4.5 and -4.0 seconds. The speed then shows a speed of 1.9 MPH at -3.5 seconds and then 0 MPH at -3.0 seconds. After the -3.0 seconds the speed is accelerated rapidly. The speed goes 0 MPH at -3.0 seconds to 23 MPH at the crash (0 seconds). The speed from has a margin of error of +/- 4%. This means that the Nissan was traveling 22.08-23.92 MPH at crash (air-bag deployment). This scene roadway evidence did not have any side-slipping or acceleration skids. The body-worn camera footage shows the Nissan backing up slowly then coming to a stop at -3 seconds, before accelerating forward.

The vehicle data corroborates the Shot Spotter and body-worn camera analysis, that all gunshots occurred within 3 (three) seconds.

Internal Personnel Files

As part of its investigation, DCRPT did subpoena Officer Ieradi’s internal personnel files. However, those records did not change DCRPT’s legal analysis and, under State law, may not be released to the public.1

1 See 11 Del. C. § 9200(c)(12): “All records compiled as a result of any investigation subject to the provisions of this chapter and/or a contractual disciplinary grievance procedure shall be and remain confidential and shall not be released to the public.”

Documents

- Morgan, Lewis & Bockius Report on January 13, 2021 Use of Force by New Castle County Police Department

- DCRPT Factual Addendum

- Shot Spotter Report

- Forensic Firearms Report

- Toxicology Report and Toxicology Letter

- Vehicle Crash Data

Videos

Viewer discretion advised. Because of their graphic nature, these videos are age-restricted and may not play in their embedded form. Users may need to click through and watch on YouTube.

Body-worn camera footage from Officer Ieradi

Body-worn camera footage from Corporal Ellis

Body-worn camera footage from Officer Sweeney-Jones

Expert reconstruction of events